East District School - Although several independent schools for African Americans were established during the Reconstruction period, publicly funded schools for these students did not open until the early 1880s. In Galveston’s east end, African American children attended the East District School located on Broadway between 9th and 10th streets. Grades first through seventh were taught at the single campus.

East District School Class Photo - When the Great Storm of September 8, 1900 struck Galveston Island, the East District School—a frame building—was completely destroyed.

In the Fall of 1901, a house at 13th and Avenue M 1/2 was rented to conduct East District classes until a new four-room schoolhouse was built.

The Barnes Institute, ca. 1870 - Sarah Barnes, a white female missionary, established a school for freed slaves in Galveston in 1868. In addition to educating African American children, the school provided Bible classes for adults as well as training for teachers. The Barnes Institute was located at Avenue M near 29th Street.

West District School - Under Galveston’s segregated public school system, African American children who lived on the (then) western end of the island attended West District School. The two-story, six-room brick building formerly housed the Barnes Institute. A larger frame building was later constructed, and the school relocated to Avenue M1/2 and 35th.

West District School Class Photo, 1910 - This photo shows teacher Viola Scull Fedford (left) with her class at West District School. Fedford’s daughter, Izola Collins, donated the photo to the archives of Rosenberg Library. Mrs. Collins was a longtime educator, musician, and the author of Island of Color: Where Juneteenth Started.

West District School Faculty, 1935 - During the early 20th century, black teachers in Galveston’s public school system were paid 20% less than their white counterparts. In 1943, Jessie McGuire Dent challenged the Galveston Independent School District over this matter in a case which she ultimately won. After that time, black teachers received equal pay in Galveston.

This photo was taken by John E. Palmer, an African American photographer who operated a studio in Galveston for several decades until his death in 1964.

School Play, George Washington Carver Elementary School - The East and West District Schools reorganized in the 1930s. The school on the eastern end of town became known as Booker T. Washington and was located at 27th and Avenue M. The West District School evolved into George W. Carver School along 35th and Avenue M 1/2.

Crosswalk at George W. Carver Elementary School - After Galveston’s schools were integrated, Booker T. Washington and George W. Carver were consolidated into a single campus at the Carver site. It was renamed in honor of Dr. Leon A. Morgan who served as principal of Central High School from 1941-1967. Morgan Elementary still operates on the site today.

Flag Raising, George W. Carver Elementary School - When Boy Scouts of America was established during the early 20th century, the organization adopted the same system of segregation followed by the nation’s public schools. African Americans were allowed membership, but troops were separated by race. Troop 116 of Carver Elementary School was active for several decades until integration

Central High School, ca. 1905 - Established in 1885, Central High School was the first high school for African Americans in the state of Texas. The school was initially housed in a rented frame building near the corner of Avenue L and 16th Street. In 1893, the well-known Galveston architect Nicholas Clayton designed an attractive two-story brick building with multiple classrooms on the 2600 block of Avenue M. The original structure was later demolished, but the 1924 annex still stands and today is home to the Old Central Cultural Center.

Central High Graduates, 1893 - John R. Gibson (seated in center) became principal of Central High School in 1889, after its first principal, C.J. Waring, relocated to Chicago. Mr. Gibson served in this capacity for nearly five decades until his retirement in 1936.

Central High School Band, 1915 - Central High School’s Bearcat Band was legendary both in Galveston and throughout the state of Texas. Central High received numerous awards and accolades for marching and concert performances throughout the school’s history.

Central High School Marching Band in Parade - In addition to performing at football games, the Bearcat Band was often invited to participate in local parades and civic events. Many of Central High School’s band members went on to play music on a professional level as adults.

Central High Athletic Staff - A native of Waco, Texas, Coach Ray “Tuck” Sheppard was a star of the Negro National Baseball League for two decades in the early 20th century. Though white and black teams were segregated in the U.S., Sheppard had opportunities to play against Major League greats Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig outside of the country. Ray Sheppard came to Galveston in 1931 to coach Central High’s outstanding football and baseball teams, and his tenure lasted until 1969.

Central High Baseball Team Photo (undated) - This image features a baseball team from Central High School. In 1962, the school won the state championship for baseball.

Central High Football Team Photo (undated) - During its 83-year history, Central High School was recognized for excellence in both academics and athletics, with many state championship titles awarded in sports. After a number of years without a state win, the 1964 Central High School football team successfully defeated Dallas Madison to become Texas State Champions. It was the last big win before Central High was closed after integration in 1968.

Galveston’s Lunch Counter Sit-In Movement - While a junior at Central High School, Kelton Sams initiated the lunch counter sit-in movement in Galveston. These peaceful student demonstrations led to the successful integration of island lunch counters in 1961. After graduation, Sams enrolled at Texas Southern University where he was elected student body president. He has remained active in religious, political, and economic affairs in the Houston area and nationally since leading the lunch counter sit-ins.

The Colored Branch of Rosenberg Library - Shortly after the opening of the Rosenberg Library in 1904, a separate “Colored Branch” for African Americans was established. It is believed to be the first public library for blacks in the southern United States. The Colored Branch was housed in an annex to Central High School, the first African American high school in Texas.

Lillian Davis, Librarian - Lillian Davis served as the Librarian for the Rosenberg Library Colored Branch from the 1920s through the 1950s. Ms. Davis was admired by students and highly regarded by administrators at the main library.

The caption on the back of this June 1946 photo reads:

Roberta Woolbright, Central High School Student, is pictured here receiving congratulations from Miss Lillian Davis, Librarian at the Rosenberg Colored Branch Library, for winning a $25.00 United States Savings Bond for her prize-winning essay on “Why Galveston Should Support the Rosenberg Library.”

Avenue L Baptist Church - In 1840—just one year after the City of Galveston was officially incorporated—members of the all-white First Baptist Church established a separate congregation for slaves. Later called the Colored Baptist Church, this congregation eventually erected its own building at Avenue L and 26th Street.

Choir Group, Avenue L Baptist Church - In the years following the Civil War, membership grew from 47 to 500. However, tragedy befell the congregation in September 1900 when a powerful hurricane devastated Galveston Island. The church building was lost and many members of the congregation lost their lives during the storm. The church’s current name, Avenue L Baptist Church, was adopted around 1903 as the church began to reorganize and rebuild itself.

West Point Baptist Church - West Point Free Missionary Baptist Church was organized in 1870. The congregation did not have its own building, so services were held in various locations. In 1916, construction began on the current church located at 3009 Avenue M.

Shiloh A.M.E. Church, Easter 1910 - Though Reedy Chapel A.M.E. had existed in Galveston since the 1840s, by the 1860s a second A.M.E. church was needed to accommodate the increasing number of African American residents who lived west of 25th Street. Shiloh A.M.E. Church was constructed at 1310 29th. Hurricanes in 1894 and 1900 destroyed earlier buildings, but the present structure dates to 1923.

Loading Cotton - After the Civil War, many African Americans in the port city of Galveston found work as longshoremen, loading and unloading cargo on ships. Bales of cotton were wound as tightly as possible with specialized screw jacks before being placed in the holds. Known as “cotton jammers” or “screwmen” these laborers created their own powerful union in 1879 after being denied admittance into the white union. Known as the Cotton Jammers Association, the group established a park near 37th Street and Avenue S which provided a venue for special events and celebrations for the African American community.

Wiley-Nicholls Cotton Truck - This image—taken during the 1925 Midsummer Carnival historical pageant and parade—shows a man driving one of the earliest types of cotton trucks used in Galveston. By the time the photo was taken, these simple horse-drawn wagons had been replaced by motorized trucks.

Segregated Beaches - Before the 1960s, Galveston’s beachfront was segregated. Whites enjoyed swimming and beach recreation on the east end of the island, while African Americans did the same on the west end. There was, however, a one-block stretch of beach on the eastern side of Galveston which was open to black residents. Between 28th and 29th Street along Seawall Boulevard stood several popular black-owned businesses including Gus Allen’s Villa, the Jambalaya Restaurant, and the Manhattan Club.

Armstrong’s Drugstore and Kenyon Auto Supply - Thomas Deboy Armstrong was born in Louisiana in 1907; the family later moved to Texas. Armstrong graduated from Prairie View College in 1929 and settled in Galveston with his wife, Marguerite, in 1938. In addition to a drugstore, the Armstrongs owned the adjacent Kenyon Auto Supply.

Interior of Armstrong’s Drugstore - Opened in 1946, Armstrong Drugstore was a popular hangout for African American residents. In addition to a pharmacy, the store was equipped with a lunch counter and a jukebox.

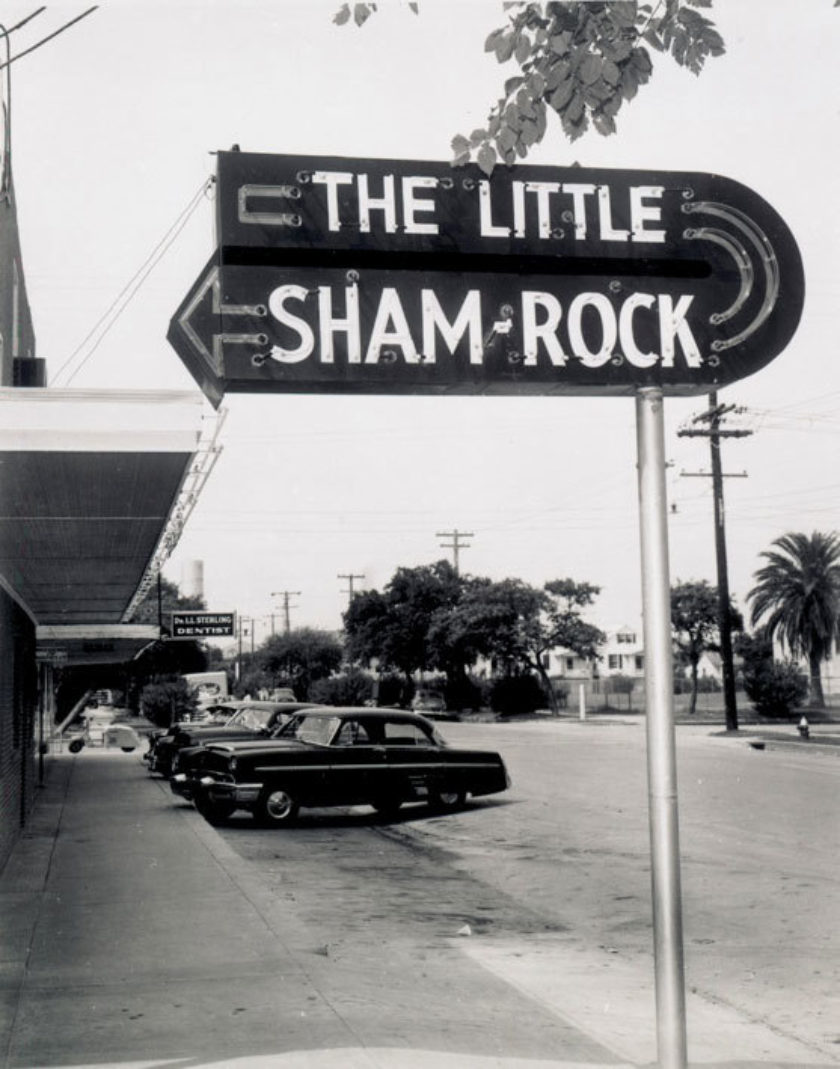

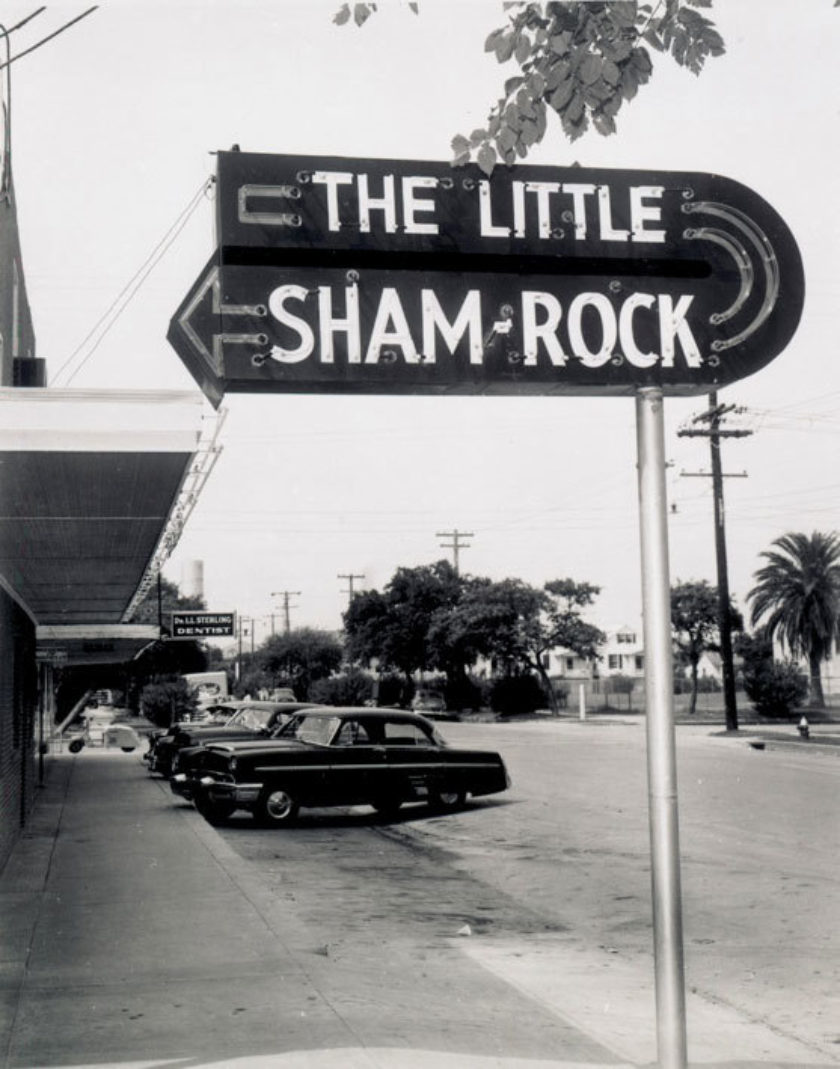

Little Shamrock Hotel and Sterling Dental Office - Six years after opening Armstrong Drugs, the family built the nearby Little Shamrock Hotel. The second floor of the Armstrong Drugstore was occupied by Dr. Leroy Sterling, a prominent African American dentist who operated an office in that location for more than ten years. Dr. Sterling also served as the official dentist for Galveston’s African American schools.

Coffee Shop at The Little Shamrock Hotel - A coffee shop and lounge were added to The Little Shamrock Hotel in 1956. The entrepreneurial Armstrong family also owned a washateria, an insurance company, and a funeral home.

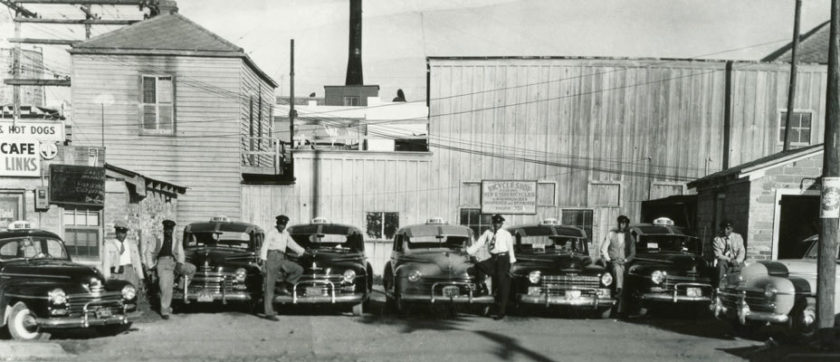

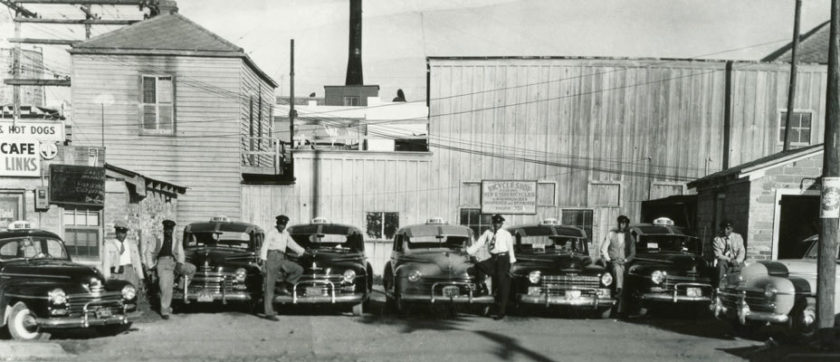

Busy Bee Cab Company - Busy Bee Cab Company was founded in 1945 by Theodore (Ted) Langham, Sr. It was located on the 2700 block of Church Street along with other black-owned businesses. Langham’s son, Ted, Jr., later took over the family business. Busy Bee continues to provide taxi service on the island today.

Shoeshine Parlor - The staff of a shoeshine shop located on the 2700 block of Church Street poses for a photo. This shop was located adjacent to a concentration of black-owned businesses in downtown Galveston including Savoy Beauty Shop, Gus Allen’s Hotel, and Honey Brown’s Barbecue.

Seller’s Barber Shop - This image shows the interior of Sellers Barber Shop, owned and operated by Eldridge Sellers, Jr. The shop was located at 3413 Avenue H (Ball Street).

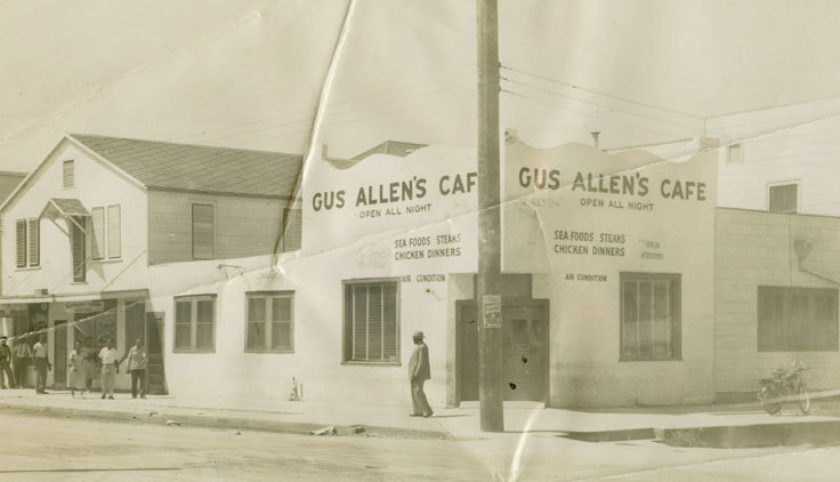

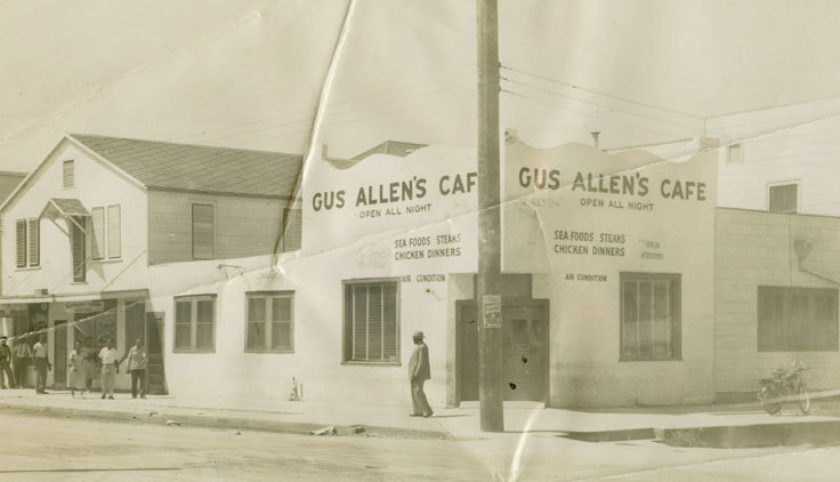

Gus Allen’s Cafe - The grandson of a slave, Gus Allen was born in Louisiana in 1905. In the early 1920s he came to Galveston and got a job shining shoes for guests at the Hotel Galvez. In 1930, he opened his first café at Church and 27th Street.

Gus Allen’s Hotel - Within a few years, Gus Allen opened a hotel in downtown Galveston. During the 1940s, Allen opened additional businesses including the Manhattan Club near 29th and Seawall Boulevard—the only section of the beachfront that African Americans were allowed access to during segregation.

Honey Brown’s Barbecue Pit - This photo shows Gus Allen (far right) with the staff of Honey Brown’s Barbecue. The restaurant was located at 28th and Church, near several of Allen’s own businesses. Nelson “Honey” Brown and his wife, Edna, operated the restaurant from the 1940s until his death in 1979. The well-known eatery was popular with both black and white customers.

Original Holy Rosary School, late 19th century - Opened in 1886, Holy Rosary Catholic School was one of the first parochial schools for African Americans in Texas. Within just two years, the original one-room schoolhouse became inadequate for the quickly growing student body.

Holy Rosary Expanded Campus, late 19th century - A larger school was built at 25th Street and Avenue I followed by a parish church, also called Holy Rosary, to serve Galveston’s black Catholic community. The school operated for 93 years until closing in 1979.

Holy Rosary School and Church, early 20th century - Established in 1889, Holy Rosary Church was the first church dedicated to serving African American Catholics in the state of Texas. Initially located on Avenue L and 25th Street, Holy Rosary Church moved to Avenue N and 31st Street in 1914. A new church was built on the site in 1958, and today it continues to operate as part of Holy Family Parish of Galveston and Bolivar.

“Uncle Newton” - Newton Taylor (also known as “Uncle Newton” and “Old Doc”) was born around 1828 in Mississippi, likely into a slave family. He later came to Galveston and was hired by Rev. Stephen Bird of Trinity Episcopal Church to be the church’s organ blower and grave digger. Taylor was a member of Holy Rosary Catholic Church and was well known in community. He is believed to have dug hundreds of graves for deceased Galvestonians, and he always attended their services as a mourner. He died in 1905 and is buried in an unmarked plot at the Old Catholic Cemetery.

John Sealy Hospital and the Negro Hospital - This photo shows the grand 1890 John Sealy Hospital with the smaller frame “Negro Hospital” to the rear. The Negro Hospital lacked basic amenities provided to white patients in the main building. To address these inequities, a group of black women formed the Colored Women’s Hospital Aid Society to raise funds for the purchase of new hospital beds, wheelchairs, patient gowns, and infant cribs, among other projects. The Negro Hospital closed in 1953 after the construction of a new John Sealy Hospital which included a segregated wing. During the 1960s, John Sealy Hospital eliminated this practice and all hospital facilities became fully integrated.

Black Health Parade, 1938 - John Clouser, a local educator, created the Volunteer Health League in the 1930s. The goal of this group was to educate the African American community about best health practices. Each year during National Negro Health week, parades, lectures, exhibits, and other events were held to promote nutrition and exercise while dispelling fear and mistrust of doctors and hospitals.

Dr. Mack J. Mosely - In Galveston, African American physicians did not have admitting privileges at John Sealy Hospital and could not perform surgery or care for their patients while hospitalized. Instead, these doctors could only see patients through their private practices, many of which were located along Postoffice or Market Street west of 25th Street.