When the United States Constitution was written in the 18th century, it did not guarantee women the same voting rights and protections as men. It wasn’t until 1920 when the 19th amendment was ratified, that women were legally granted the right to vote. Gender and sexuality impacted every social, personal, and political component of the suffrage movement that parallels contemporary women’s equality movements. While a majority of this movement was happening on a national scale, this history is also reflected in the activities of the Galveston Equal Suffrage Association. Reflecting on the 102nd anniversary of the 19th amendment, this blog post will explore how women of the 19th and 20TH century suffrage movement challenged normative gender constructs of their time. My hope is to provide a lesser known perspective to the suffrage movement while highlighting non-heteronormative and non-binary history.

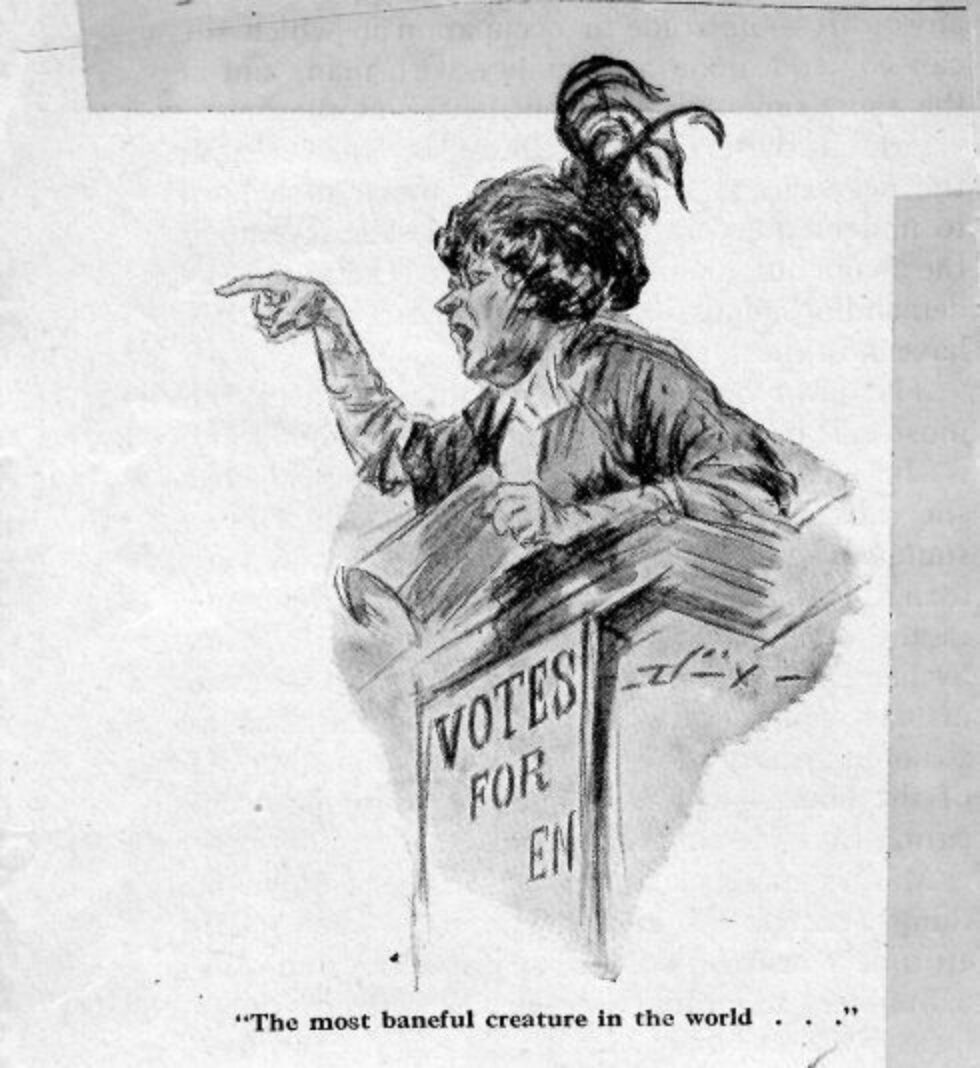

In the 19th century, traditional Victorian beliefs of true womanhood policed gender roles—women were expected to be submissive, passive, delicate, feminine, obedient, and dutiful daughters, mothers, and wives. However, not all suffragists had the desire to remain limited to the domestic sphere. In order to live the life they wanted and pursue the change they wanted to see in the world, they had to be outspoken and make their opinions known. But when they did so, the media began depicting suffragists as masculine to deter women from joining the movement, labeling them as “mannish,” gender inappropriate, or ineligible for a husband because they wished for a place alongside men. This was significant as Victorian constructs limited women’s ability to make their own individual incomes, independently own property, or have equal access to everyday opportunities. Finding a husband often became a matter of social and economic survival. The defamation of suffragists created a hostile environment for women, promoting a false dichotomy—suffrage and equality, or, traditional womanhood and confinement to the paradigm of a conventional marriage.

Despite this, leaders, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, became more outspoken about women’s equality after a discriminatory experience at the World Anti-Slavery Convention of 1840 in London, England. Delegates of the convention asked the women in attendance, all dedicated abolitionists, to sit separately and hidden from the men—blocking their ability to participate and have a voice in the matter. This blatant separation and discrimination prompted the women to form the first women’s rights convention in 1848, known as the Seneca Falls Convention. The convention produced the “Declaration of Sentiments,” outlining women’s entitlement to equal citizenship. The only item on the convention’s agenda that did not unanimously pass was women’s right to vote. While surprising to us now, this right was viewed as too controversial, with the potential to halt support for the movement. After much debate, including persuasive arguments from Frederick Douglass, the resolution for women’s right to vote was eventually passed, marking the beginning of an organized campaign for woman suffrage in the United States. From then on, the tactics used by suffragists challenged every notion of femininity and traditional Victorian ideals. However, opinions on how to achieve suffrage became controversial and eventually divided the movement.

The two emerging suffragist organizations were the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and the National Woman’s Party (NWP). NAWSA was led by Anna Howard Shaw, who was “powerfully assertive when passivity was the norm for women.”[1] Despite Anna’s preference to defy femininity in her private life, she publicly shaped her persona to be feminine by growing out her short hair after negative remarks. Also publicly known for her whimsical persona, smart and sound mind, and feminine charm, antisuffragists were threatened by Anna because of the challenges she posed, proving that a woman could be feminine, assertive, powerful, and successful alongside men.[2] Anna used her abilities to shape NAWSA into the “good cop,” of the movement, making diplomatic speeches to reluctant supporters who were “already terrified by the uncontrolled potential of women that suffrage seemed to threaten.”[3]

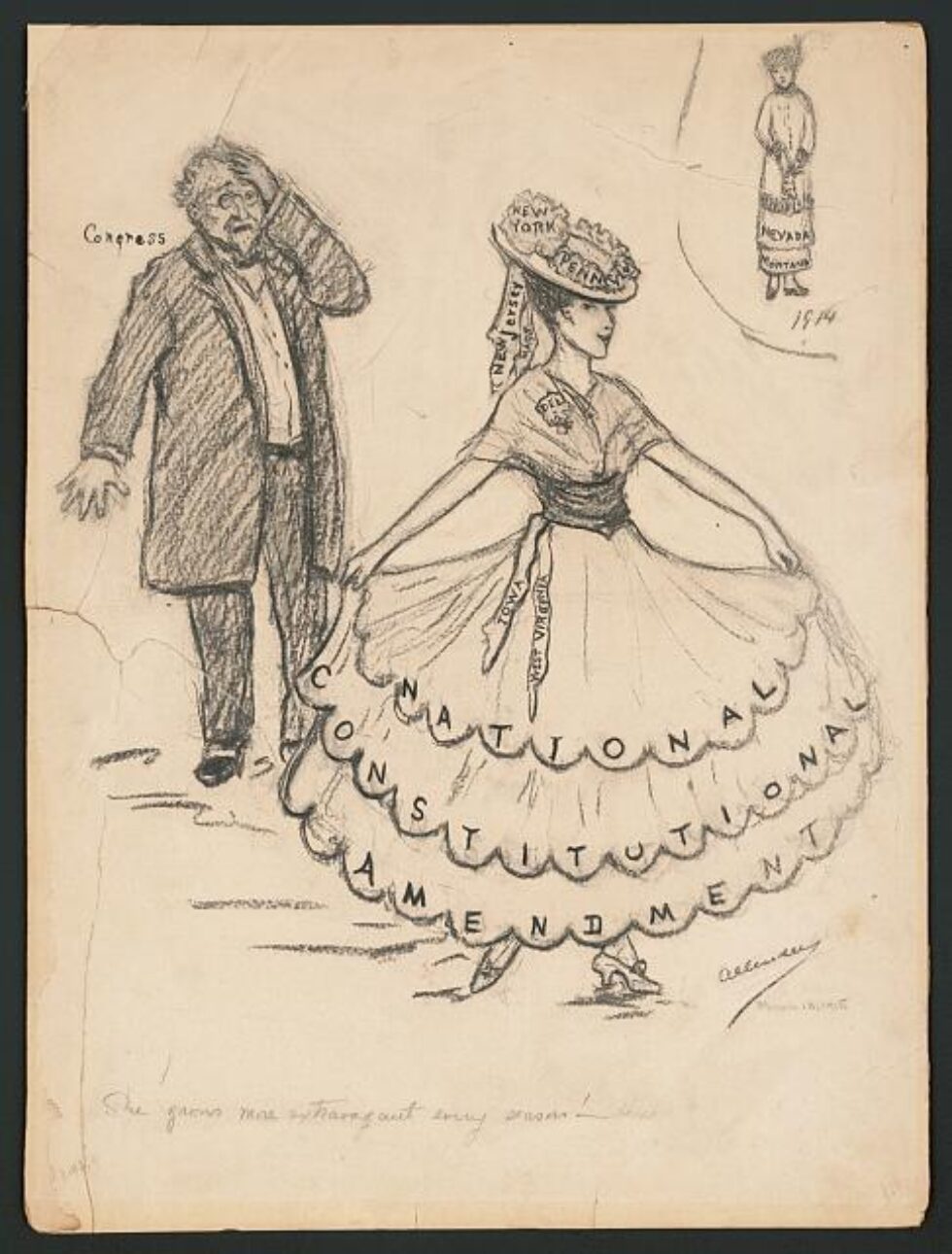

In contrast, the NWP, led by Alice Paul used tactics that were considered aggressive and militant at the time, contradicting traditional Victorian ideals. A former Quaker, Alice Paul was radicalized by the British suffrage movement which shaped her path of discourse and discontent with President Wilson and the U.S. Government. Suffragists began picketing outside the White House, becoming the first political activists to implement this practice. Picketing and outward criticism of President Wilson was viewed as unpatriotic or even seditious by many amidst World War I. This fueled the NWP’s arguments and they used President Wilson’s own words against him on banners, highlighting the hypocrisy abroad while denying women to vote at home. By 1917, suffragists picketing outside the White House were arrested on the charge of obstructing traffic. These women were imprisoned in unsanitary conditions and were often beaten, force fed, and assaulted. This meant suffragists risked their health, social status, jobs, money, and reputations by continuing to protest and picket.

NAWSA believed the NWP was reinforcing the antisuffragist propaganda that portrayed suffragists as masculine, rowdy, and uncivilized. The NWP pushed back on this by publishing political cartoons from 1914–1927 using the “Allender Girl.” Portrayed as feminine, young, slender, energetic and capable, the Allender Girl was opposite of the mainstream media’s propaganda. Moreover, the Allender Girl represented a variety of women—feminists, wives, mothers, students, and activists. Use of the political cartoons gave the NWP the ability to take back their narrative and provided women with a positive, self-respecting, and independent role model.

Challenges to traditional gender roles and Victorian ideals stretched beyond political cartoons, conventions, and the media. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, women were increasingly becoming college-educated and expanding their economic opportunities. For instance, Minnie Fisher Cunningham was the first woman in 1901 to earn a Graduate of Pharmacy Degree from the University of Texas Medical Branch. However, frustrated by pay inequality, she quit her job and dedicated herself to social reform and equal rights. By 1912 Minnie Fisher Cunningham became a founding member of the Galveston Equal Suffrage Association, and elected to President of Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) in 1915. While Minnie Fisher Cunningham had a conventional marriage, many other women across the country remained unwed after graduation and moved to the nation’s largest cities, becoming involved in political activism such as the suffrage movement.

Moreover, many women practiced same-sex love and desire—maintaining successful same-sex partnerships that helped elevate their cause. This is often referred to as a Boston marriage, a practice increasingly popular in New England during the 19th and 20th centuries, where women could cohabitate and be financially independent from a man. Boston marriages could be women in same-sex relationships with romantic desire, or two women maintaining a platonic friendship. Nevertheless, these acts of receiving higher education, attaining economic independence, remaining single, and building same-sex partnerships dismantled almost every notion of traditional Victorian beliefs and popular ideals of true womanhood.

[1] Lillian Faderman, “To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have done for America- A History,” (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999), 17..

[2] Faderman, 40.

[3] Faderman, 55.

Written by Ivy Albright, Museum Curator. For more information, please call 409.763.8854 Ext. 125 or at museum@rosenberg-library.org.

For press, please contact Janae Pulliam, Communications Coordinator 409.763.8854 Ext. 144 or Communications@Rosenberg-Library.org.